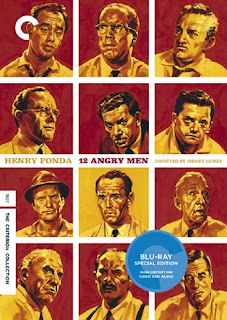

12 Angry Men (1957)

It's hard to explain why, but I really like courtroom dramas. Maybe it's the figure of the prosecution attorney trying his best to bring justice to the table (see Paul Newman in the excellent The Verdict), or the defense attorney fighting with all his might to release the defendant we as the audience know is innocent (e.g. Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird, a movie loved by many, many people -- myself included --, but clearly not by Ebert), or maybe the battle of wits between both sides (check out Spencer Tracy and Fredric March in the superb Inherit the Wind). Well, Sidney Lumet's 12 Angry Men has nothing of the above. Well, not explicitly, at least.

Based on a 1954 teleplay by Reginald Rose, the movie starts when the trial per se is over, with the judge addressing the jurors before their deliberation. The accusing parties seem happy, as if a guilty verdict was certain; the defense lawyer, leaving the courtroom, seems to have had a difficult time during the trial; the defendant looks confused and exhausted. We have not listened to the final remarks of either lawyer, thus we are not capable of taking our own conclusions from the start, having all we know filtered through the jurors, tainted by their experiences, their emotions, their prejudices. Twelve nameless strangers are locked in a room on the "hottest day of the year", never to meet each other again after the trial, deliberating on whether an 18-year old kid should be executed for allegedly stabbing his own father to death. Eleven men are certain of his guilt; Juror #8 (Henry Fonda), nonetheless, is not so sure.

|

| Juror #8 (Henry Fonda) raising his hand |

Through the deliberation of the jurors, we learn that the defense attorney didn't seem to be getting any Lawyer of the Year award any time soon. We are presented with plenty of circumstantial evidence on the boy's guilt: we learn the boy had had another fight with his father in the same night the crime took place; we see the switchblade used in the crime, which looks exactly like the one the boy had just bought after the fight; we learn of an elderly neighbor who allegedly saw the boy running downstairs after the crime. One piece of evidence seems crucial, though: a front-door neighbor testifies she saw the boy do it. Even with the movie skewed toward Juror #8, that piece of evidence made me stand by Juror #4 (E. G. Marshall) the first time I watched it: even with all other data discarded, someone had actually seen the boy doing it! It's hard to argue with that...

|

| Juror #10 (Ed Begley) in the foreground, sitting down |

One by one, all evidence is put into reasonable doubt; one by one, jurors start changing their opinions. Jurors #4 and #3 (Lee J. Cobb), however, remain adamant: the former due to the front-door neighbor's testimonial; the latter, we see later on, due to his own prejudices. In fact, two of the most remarkable scenes are, for me, when they both finally change their minds. Actually, with so many memorable scenes to choose from, the ones who stand out the most, in my opinion, involve either jurors #3 or #10 (Ed Begley). For the former, pretty much every time he's on frame he's great to watch, with his final scene (when he realizes at last his own motives for having wanted the accused to be executed) being so heartbreaking it made me cry the first time I watched it (and in some viewings after that, to tell the truth). For the latter, even though I love watching him being put in his place by Juror #11 (George Voskovec), I have to go with the scene where he starts to vociferate about "those [slum]people" and, one by one, the jurors stand up and give him their backs. By having been raised in a not-so-bright side of Brazil myself, he really managed to get in my nerves with that rant (kudos to the actor, director, and screenwriters for that).

|

| Juror #4 (E. G. Marshall) |

As I mentioned in my post about Casablanca, whenever you watch a movie several times, you start noticing details you hadn't before, and that is a good thing. On the other hand, the element of surprise of the first time watching that movie is lost forever. Some people say you can see a movie "for the first time once again" by watching it with someone else, but I find it's not the same... That is why I was so happy when a paper by Charles Weisselberg was brought to my attention: by reading it, I was able to appreciate 12 Angry Men from a different point of view. In his paper, titled Good Film, Bad Juror, he, a Law professor at UC Berkeley, goes on about the several misconducts in the movie that could actually have given argument for mistrial: a lot of information that refutes testimonials given under oath were brought up during (and even introduced, as when Juror #8 brought a switchblade he himself had bought at the crime scene neighborhood) during their deliberation, having thus not being cross-examined or even rebutted by the involved parties. This may not seem like a big deal, but, for me, it opened a whole new panorama of approaches for the movie. For the first time, I could watch it having "privileged, inside information" about the actual jury proceedings, and that felt nice :-) Also, questions like "what if the uncross-examined evidence had led to a verdict of guilty instead of acquittal?" had come to my mind. I mean, it's a capital case after all! What if someone had said to Juror #8, "you can't do that!"? How would the pieces of evidence be, or could they be, contested? Would it still lead to acquittal? But I digress...

On a lighter side of the matter, there is also a very funny adaptation of 12 Angry Man made in 1991 by Shun Nakahara called 12人の優しい日本人 (12 Kind Japanese), where a woman is on trial for accidentally pushing her husband in front of a truck, leading to his death. In this movie, though, eleven jurors are sure of her innocence; one juror, however, raises serious questions about whether the accused isn't, in fact, a cold-blooded murderer, gradually convincing his fellow jurors -- nice people who wouldn't think poorly of anybody -- to change their minds. The main point of the movie is to put the effectiveness of the trial by jury into question, as the concept of a jury was completely foreign to Japanese people by then (such trials have been relaunched in Japan as recently as 2009 after a hiatus of over 60 years). It also spoofs the Japanese tendency of not being assertive nor expressing their own opinions, which goes against any productive discussion. Even though this is a pretty good movie (in my opinion, anyway), it has not been released outside of Japan as far as I know...

Summarizing it:

Liked

|

Didn't like

|

|---|---|

Everything, especially Juror #3

|

Can't think of anything.

|

The best line from the best scene, by Juror #3 [SPOILERS]:

Great Movie review by Roger Ebert here.

If you liked this movie, then make sure to watch Stanley Kramer's Inherit the Wind (1960), probably the best courtroom drama I have ever watched. Also, maybe try watching Jonathan Lynn's My Cousin Vinny (1992).

Comments

Post a Comment