Ivan the Terrible is the perfect example that a movie is not made in a vacuum, being shaped instead as the result of its director's handling of external pressures. In the case of

Sergei Eisenstein, even though he had to struggle with having his revolutionary ideals crushed by the power of

Joseph Stalin and his creative process restricted by the draconian rules of

Socialist Realism, he still managed to create (albeit not to finish) a daring story about a paranoiac leader in a a diseased surveillance state while living in Stalin's USSR.

The trilogy chronicles the life of Czar Ivan IV (

Nikolai Cherkasov) from his ascension to power, in Part I, going through his confrontation with the aristocracy, in Part II, up until his acquisition of absolute power over a unified Russian state, in Part III. As friends and family plot against him, he grows increasingly paranoiac, being ultimately forced to become the tyrant he is now known for, learning that with great power comes not only great responsibility, but also unbearable loneliness. Part I, in perfect accordance with Socialist Realism much like

Alexander Nevsky (1938), focuses on a resolute and adroit Ivan, exercising his mightiness by winning wars, gaining the love of the people (such as the commoner

Malyuta - Mikhail Zharov -, who becomes his personal bodyguard and "watching eye") and overcoming his enemies in the ruling nobility, the

boyars. These include his aunt Efrosinia (

Serafima Birman), who wants her half-wit son

Vladimir (Pavel Kadochnikov) to sit on the throne, his closest friend Kurbsky (Mikhail Nazvanov), lusting not only for power, but also for Ivan's wife, Czarina Anastasia (

Lyudmila Tselikovskaya), and Archbishop Pimen (

Aleksandr Mgebrov), not happy with Ivan's taxation on the church. Part II, on the other hand, is centered around Ivan's dealing with the side-effects of power, clashing his moral values against the cruel actions he is forced to take in order to remain in power, which in turn lead to momentary reactions of doubt and regret (reason why Stalin accused him of being "

a spineless weakling, a Hamlet type").

|

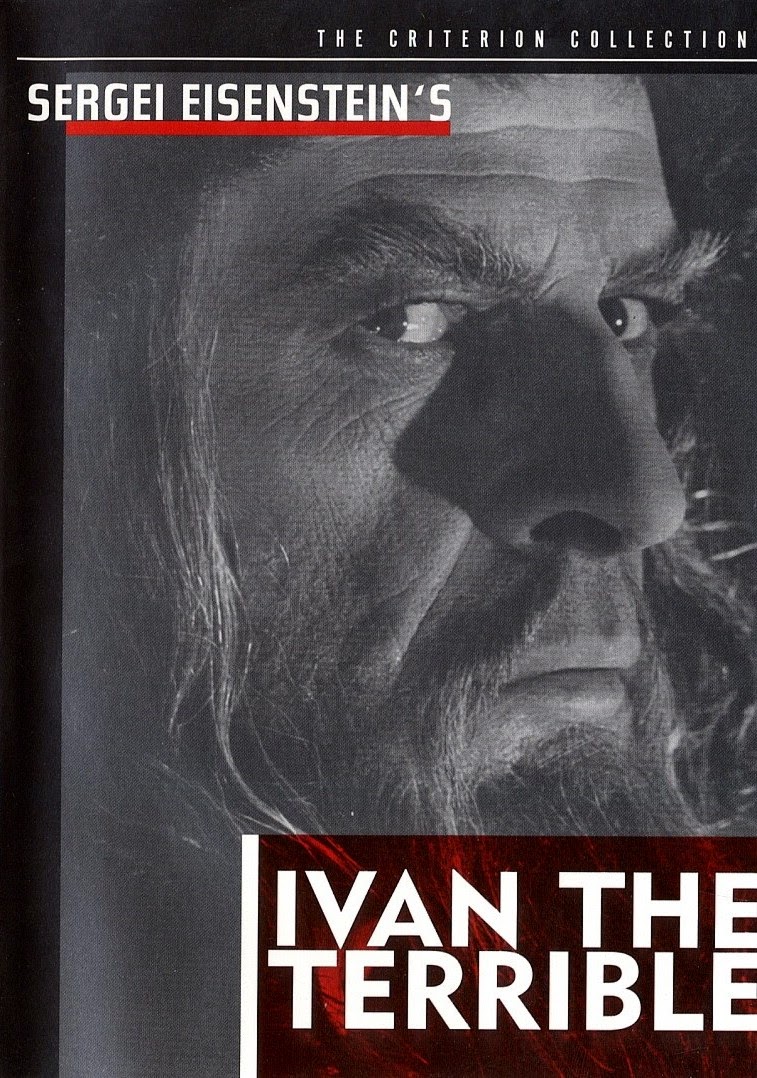

| Nikolai Cherkasov as Ivan, breaking the fourth wall |

It is impossible, though, to comment on

Ivan the Terrible without first talking about its director. Eisenstein was a Communist Revolutionary, having actively participated in the October 1917 revolution which terminated the reign of the House of Romanov. His marvel at the possibilities of Socialism abounds in his earlier movies

Strike (1925),

Battleship Potemkin (1925) and

October (1928), all of which depict peasant masses who, tired of being exploited by the elite, come together to successfully change the status quo. After

Lenin's death, however, Eisenstein saw those possibilities crushed one by one by Stalin's bloody reign. Granted a special permission to make a film in Mexico, upon returning to the USSR he was seen with great distrust by the party members, which, along with the enforcement of the

Socialist Realism limiting greatly what artists were able to express, contributed for his less-than-stellar productions at the time. Having then been given a second chance by Stalin himself, he chose the least controversial subject possible, the story of national hero

Alexander Nevsky (1938), for his next project. Ironically, that movie ended up being released it in the same year

Boris Shumyatsky, a key member of the Soviet film industry, was shot dead as a traitor for not abiding to the new ideas in Soviet film-making. In such dreary times, even tough the glorification of the individual rather than the masses was in clear contradiction with his earlier work, Eisenstein chose a biography once again for his next picture, this time that of the first Russian Czar (and Stalin's personal hero), Ivan the Terrible, to be shot as a trilogy. Even though Part I was met with great acclaim, Part II, for dealing with touchier subjects, was the target of much controversy from the start. Several members of the crew, fearing danger for their lives,

allegedly left the project during its shooting , and Eisenstein, even after being forced to write several articles of self-criticism, was summoned by Stalin himself for

a hearing concerning the film. Nevertheless, Part II ended up being banned by the Party shortly after its release for being "

anti-historical and anti-artistic". Eisenstein died soon after that, in 1948, soon after having started working on the final part of the trilogy. Part II was finally released to the public in 1958, five years after Stalin's death.

|

Ivan being crowned Czar of all Russias,

bathed by divine light inside the Cathedral

|

|

|

Light still glows over Czar Ivan as he addresses

his subjects for the first time

|

|

|

Ivan as if radiating light, in the midst of a mob who

until moments ago was bent on killing him

|

|

|

Ivan at the top of a hill, stripes of clouds emanating from him, making him

look like the sun

|

|

Ivan is first presented to the audience as a gift from God, being bathed by divine light inside a Cathedral whose windows we are not even sure exist. During his speech following the coronation, while we are presented to the whole cast of his enemies in extreme close-ups to make us feel less at ease, god rays still shine over Ivan, as if to reassure us he is the one ruler who will overcome them all. In addition, during Ivan's wedding feast, as the city burns by the orders of his aunt Efrosinia, when an angry peasant mob storms the castle bent on killing him, he manages to turn them to his side by the power of his word alone. In this scene, Ivan is framed completely bathed in light, his white gown making it seem as if light is actually emanating

from him toward the crowd. Such idea of Ivan as the ideal leader is further reinforced during the Battle of Kazan, in which he is always depicted standing on a hill overseeing his men, light rays now emanating from him as if he were the sun itself. He only comes down to the same level as his men to correct

Kurbsky's ruthless behavior, as a true leader would.

|

Ivan's gigantic shadow shown in contrast to the

diminutiveness of those of the treacherous boyars |

|

|

Notice, compared to the image on the left, how the lighting in this

shot has been manipulated so that Ivan's head now projects a huge

shadow onto the wall |

|

|

Ivan is shown here greater than the world, much like a god,

giving instructions to his servant |

|

|

This beautiful shot shows Ivan walking toward the room in which

his wife lays asleep, his shadow shrinking from that of a god

to that of a common man |

|

All Ivan wants is for Russia to be a powerful state, and the first step toward that goal is recovering all former Russian territories annexed by neighboring countries. The petty boyars, however, are afraid of letting him fulfill that objective, fearing it would empower him and, consequently, disempower them. The contrast between Ivan's selflessness and the boyars selfishness is visually depicted via the size of their shadows, which act as literal projections of their inner selves, their truer personas, device used when Ivan first confronts the boyars for obstructing his warring campaigns. We can see then an irate Ivan stepping down from the throne and walking among them, their diminutive shadows made to seem even smaller in comparison to Ivan's gigantic silhouette. To stress their rat-like behavior even further, the boyars are pictured fleeing the chamber via its mouse-hole-like doors (did Russian castles really have doors that small???). In the subsequent shot, the lighting of the scene is manipulated in such a way we still see Ivan's colossal shadow highlighted in the frame as he is bowed to by his ambassador, and Eisenstein also adds perspective to the mix by framing a gigantic Ivan looming over the shadows of his emissary and the iron globe on the desk, depicting him thus as a god lecturing a mortal. This sequence then ends with a beautiful shot depicting Ivan walking toward the room in which his wife lays asleep: at first, his shadow is enormous, as previously, externalizing his god-like devotion to his people as their ruler; nevertheless, the closer he gets to the door, the similar in dimension his shadow becomes to that of the emissary he just dismissed, hinting that, even though Ivan is a magnanimous leader when needed be, at the end of the day he also needs a shoulder to rest his head upon, much like any other mortal.

|

|

Use of perspective to depict Ivan as god-like,

watching over the people |

The perspective trick used to make Ivan seem god-like is also employed at the end of Part I, when, in exile, he is greeted by the Russian people begging him to return to Moscow. Ivan was waiting for that call to, in his eyes, legitimate his claim to absolute power, as "The call of the people will reveal God's will". The snake-like formation of the extras in this scene is a nice trick to make the already copious amount of people in the shot seem even more impressive. After having served its purpose for the plot, however, the people are never again seen in Part II, which, by going blatantly against the Social Realist style imposed by Stalin, contributed for its banishment.

|

| Ivan's menacing follow up to the line "a head does not fall by itself". Notice the sudden illumination change. |

|

|

| Efrosinia (Serafima Birman) plotting against Ivan. Notice again the position of the light source. |

|

|

| Archbishop Pimen (Aleksandr Mgebrov), lit in the same fashion to stress his threatening nature. |

|

|

| Archbishop Philip (formerly Ivan's friend Fyodor Kolychev - Andrei Abrikosov), also scheming against Ivan |

|

In the same way soundtracks are normally used to guide the viewer's emotions, in

Ivan the Terrible Eisenstein manages to achieve the same effect via visual suggestion. This is accomplished, however, not by explicit editing (in the same way as his

Strike - 1925 - for example, by cross-cutting from the workers being massacred to cattle being slaughtered), but by appealing to our subconscious response to visual cues from previously watched scenes. The most evident use of this device is when Eisenstein wants to make someone look menacing, effect achieved by lowering the main light source of the scene and aiming it up at that person's face, first used when Ivan says an intimidating line to the crowd he is addressing. From that point on, whenever a character is scheming against Ivan, he (or she) is illuminated in the same fashion, triggering an involuntary response from the viewer every time a looming shadow around that character's nose becomes more pronounced.

|

Ivan hinting at the audience he is merely

pretending to be dying |

|

|

Jesus' eye gazing at the treacherous Kurbsky (Mikhail Nazvanov)

making advances on Czarina Anastasia (Lyudmila Tselikovskaya) while

Ivan is on his "death bed" |

|

Another running theme throughout the movie, again exploiting the artifice of scene parallels, is that of surveillance, represented by a looming, watchful eye. At one point, Ivan pretends to be dying to uncover those in the nobility who are faithful to him. While receiving his last rites, he gives himself away to the audience by peeking out from the bible put over his head before summoning the boyars to request them to swear fealty to his baby son. At the same time, we see the giant eye of Jesus observing Kurbsky's disloyalty, as he, whom Ivan believes to be his best friend, vows to protect the Czarina from the wrath of the boyars in exchange for her love, so that they may reign together.

|

Malyuta (Mikhail Zharov) - the Czar's Watching Eye -

observes the treacherous Efrosinia and Kurbsky |

|

|

Ivan, unknowingly, bringing a chalice of poisoned water to

the Czarina. Notice how Malyuta, his "all seeing eye", is unwarily

looking the other way |

|

The theme of surveillance is once again brought into foreground right before the Czarina's death, this time to stress the fact that there is no such thing as complete oversight. Malyuta, Ivan's right arm, had been previously depicted as monitoring secret meetings of boyars plotting against the Czar. However, despite his complete devotion to the task entrusted to him by his sovereign, he fails to notice Ivan giving the Czarina a goblet of poisoned water left in her chambers by Efrosinia: he is fiercely surveying, all right, but the other direction.

Before going further into Eisenstein's masterful scene parallels, it is important to talk about the way the Czarina is handled in the movie. Other than Malyuta, whom the Czar considers his faithful "dog", she is shown as the only person to be completely devoted to Ivan, standing by his side when he is resolute and comforting him when he is feeling lost. In other words, she is the diametrical opposite of Efrosinia, who wants him dead, this glaring opposition being stressed via their costume design. Contrary to Malyuta, Ivan's servant and therefore not in the position of facing a low-spirited Czar, Anastasia is the only one with whom he can feel human, emphasized in the shot in which his gigantic shadow, the projection of his truer self, gets smaller and smaller as he approaches the Czarina's chambers. That is why her death, at the end of Part I, is a major turning point for Ivan, which also justifies the complete change of tone in Part II.

|

Ivan on his knees begging Archbishop Philip, his former friend

Kolychev, not to abandon him to solitude |

|

|

Ivan dining with his cousin Vladimir (Pavel Kadochnikov).

Eisenstein makes sure we notice the color red, foreboding tragedy. |

|

In fact, the closer Ivan comes to achieving his objective, namely a strong Russian state, the more empty of human contact his life becomes. The mighty Czar reaches the point of begging on his knees to his former friend Kolychev (

Andrei Abrikosov) - now the treacherous Archbishop Philip - for him to be by his side. With no friends left, Ivan clings to his kin, the Royal Family, even after discovering that Efrosinia, his aunt, was the one who poisoned Anastasia. It is not until the banquet scene, bathed in blood red, when Ivan hears from his drunk cousin Vladimir about the plot by Efrosinia to kill him and put Vladimir on the throne, that he finally decides to sever all human bonds and fully embrace his title of "Terrible". The tragedy augured by the abundance of red in the scene is, in fact, the death of innocence; literal with the assassination of naive Vladimir; symbolic with the shattering of Ivan's beliefs in the sanctity of his family, leading to the dissociation of his last, yet unilateral, emotional ties. By the end of the trilogy, Ivan at last achieves his goal of a mighty Russia: framed alone on the shore of the opening to the sea he just conquered, nothing but the wide blue sea in the background, Ivan's power is absolute, and, with he death of his faithful Malyuta in the battle just won, he has never been so alone (although never filmed, Eisenstein's sketches for Part III survived him).

|

Ivan as a boy, with boyars literally governing

behind his back |

|

|

Vladimir dressed in Ivan's clothes, prior to being assassinated,

now with Ivan and his loyal Fyodor Basmanov (Mikhail Kuznetsov) being

the backstabbers. Compare Vladimir's crown and eye movements.with young Ivan's. |

|

In fact, it looks like Eisenstein used the colored banquet scene, Ivan's lowest point as a human being, to mirror negatively plenty of other shots in the movie. Take for example the scene in which we see a young Ivan sitting on the throne, stupefied, gazing at the boyars in the room deciding the future of his country in ways that would benefit them the most; there is a shot in that scene in which two boyars argue about politics while standing right behind Ivan, literally governing behind his back. Now jump to the banquet scene: Ivan, knowing about the assassination plot targeting him, dresses his drunk cousin Vladimir in his clothes (which look strikingly similar to the ones he used to wear as a child), and exchanges an incriminating stare with one of his men, Fyodor Basmanov (

Mikhail Kuznetsov). Ivan is fully aware that, by dressing Vladimir as the Czar, his killer would attack Vladimir instead, thus putting an end to Efrosinia's bloodlust. Now, Vladimir is the innocent youth put on the throne against his will (observe his childish eye movements and compare them to young Ivan's), while Ivan is the sneaky nobleman manipulating him.

|

White swans in celebration of Ivan's happiest of days

|

|

|

Black swans in celebration of Ivan's saddest of days

|

|

With so many clever scene parallels in Ivan the Terrible, another one I particularly like stresses even more the moral void Ivan is in during the banquet scene. He was never shown to be happier than on the day of his wedding, in which white swans, symbol of everlasting love, can be seen in a great number decorating the banquet room. In contrast to that, in Ivan's blackest of days, as he sees himself forced to turn against his own family, the ornamental swans used then are as are black as his heart had become.

|

Yet another thing Eisenstein uses to his favor is something that film viewers normally tend to disregard: set designs on par with his film characters. At the time Pimen decides Ivan must be killed, a white fresco depicting the Angel of Death acts as his shadow. When Ivan orders Vladimir, who is dressed as the Czar, to go pray in the Cathedral, knowing fully well Vladimir would be ambushed and killed in the Czar's place, we can see a celestial being giving his blessing to Ivan, as if to reassure the audience that, even though what he is doing is despicable to his moral values, he has no choice other than to be killed himself. Once Kurbsky surrenders to the King of Poland, he is greeted by that king with a salute which mirrors the fresco in the wall, in which a knight is spearing the losing jouster. Also, once Ivan wipes out the traitors inside Russia and announces he is now planning to resume his warring campaigns to repossess all Russian soil claimed by his foreign enemies, the halo in the fresco is framed as if belonging to him. I could go on, but that would made this already long post even longer...

|

| Kurbsky gazes very theatrically into empty space, while a boyar incites him to feel envy of Ivan |

|

|

| Ivan's mother after realizing she had been poisoned by the boyars. Notice how stylized the acting is. |

|

It may seem that I have spent way too much time on Eisenstein's bravura directing in detriment of the other elements of the movie; however, the truth is there is not much else to talk about, as the remaining elements merely serve their purposes. Worth mentioning, though, are the extravagant costume design and the acting, which is beautifully theatrical. Several times characters stare into empty space while being talked to, as if on a stage, and internal monologues abound. This, evidently, was sanctioned by Eisenstein, who also makes his actors rush toward the camera several times, frequently using close-ups to make the evil characters feel more menacing, and Ivan more intimate to the audience (as his sorrowful grimace fills the frame very often). And here I am talking about Eisenstein again...

Summarizing it:

| Liked | Didn't like |

|---|

| Eisenstein's masterful direction, shot framing, light work and scene parallels | No Part III |

The wonderfully exaggerated performances by the entire cast, particularly Nikolai Cherkasov

|

Perhaps because it saddens me so much to think of how stunning the trilogy could have been had Eisenstein managed to finish it, I could not bring myself to chose with which of the images below, belonging to Part III, to close this post:

|

| Ivan on his knees before the mural of the Last Judgement, facing God |

|

|

| Eisenstein's sketch of the last scene in Part III: an absolutely powerful yet utterly alone Ivan contemplates the sea at the shore he just conquered, smoke still rising from the battlefield |

|

Great Movie review by Roger Ebert here.

If you liked these movies, then do watch Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925).

BTW, the script for all three movies can be obtained on Amazon! |

Comments

Post a Comment