While people tend to associate the

Weimar Republic only with the birth of Nazism, it was also the environment in which thrived geniuses like

Robert Wiene,

Fritz Lang,

F. W. Murnau,

G. W. Pabst,

Ernst Lubitsch and

Josef von Sternberg, directors who have helped to shape the Seventh Art one way or another, all with Great Movies selected by Ebert. I have started to talk about the prolific Weimar era with

Wiene's

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), regarded by many as the epitome of the

German Expressionist movement and the first true horror film ever made. However, even though each one of those directors has made at least a movie I simply adore, the one I esteem the most is undoubtedly

Fritz Lang, for two simple reasons:

Metropolis (1927) and

M.

By the time serial killer Hans Beckert (

Peter Lorre) makes his 9th victim, the city of Berlin has already been in turmoil for quite some time. The police, headed by Inspector Karl Lohmann (

Otto Wernicke), have deployed all their manpower to the streets, with each policeman being overworked nearly to exhaustion. Displeased by the law enforcer's frequent harassment, as well as dismayed by their inability to find any clues leading to the killer, the inhabitants of the city grow more and more weary at the fatigued police force, fueling an ever increasing social tension. Also bothered by the situation are the members of the organized crime, unable to conduct their illicit affairs due to the overwhelming presence of the "green coats" in the streets. Not being able to bare the situation any longer, they see themselves forced to catch the murderer, operation headed by Der Schränker (

The Safe-cracker,

Gustaf Gründgens), leader of the Berlin underworld.

Betrayed by the song he is always whistling when hunting for victims, Beckert is identified by the criminals and hunt down, being then forced to face a mock court organized by the criminals to be judged for his crimes. When he is about to be lynched by the angry mob present at the scene, he is rescued by the police and goes on trial. Before we can hear his sentence, the shot is cut to some of the mothers of Beckert's victims, who profess among tears, "

This will not bring our children back. One has to keep closer watch over the children! All of you!".

|

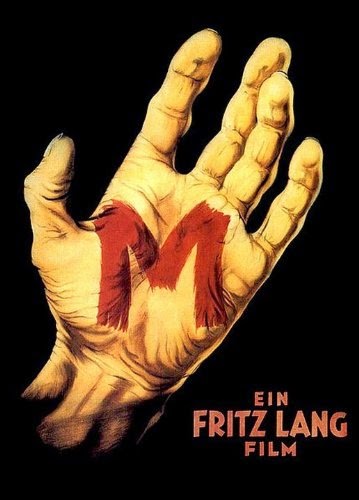

| M for Mörder (murderer) |

M is a tough nut to crack. Ebert, in his review, found it extremely anti-Nazi, and the final line of the movie alone could be used as a very strong basis for that claim. Furthermore, I am confident he knew the fact that Lang was

forced to change the tentative title of the movie from

Die Mörder sind unter uns (The murderers among us) to

M due to pressure by conservative politicians, who believed it to be "a political exposé of the Nazis". Nevertheless, a strong case supporting the fact that the movie has some very pro-Nazi undertones can also be made. Starting from its core,

Thea von Harbou, Lang's wife and the movie's script co-writer, was a Nazi sympathizer and became a party member soon after the Nazis came into power. Was she perhaps so enthralled by the coverage of

Peter Kürten, the serial killer in whose story the movie was based, not to notice the anti-Nazi themes remarked by Ebert creeping into her script via Lang? But then, since Goebbels's diaries were made public, it has been

widely known he was a great admirer of the movie and its director, allegedly offering Lang the control over the Nazi film industry. Furthermore, it was Der Schränker (

Gustaf Gründgens), the underworld leader, and not Inspector Lohmann (

Otto Wernicke), the one who actually captured the murderer. Gründgens' Schränker would fit just as perfectly well in the role of a Nazi interrogator, while Wernicke's Lohmann, upon discovering the identity of the killer, is shot from below a desk, sloppily dressed, unbuttoned trousers emphasizing his fat belly, his stance putting an uncomfortable prominence on his "manhood" compressed against his crotch, smoking a cigar while eating a piece of bread and butter, making extremely clear he is not the hero of the story - fact which

M. Tratner interprets as the proto-Nazi theme of tougher policing. Finally, being

Peter Lorre of Jewish descent, his final speech in

M was included by the Nazis in their propaganda film

The Eternal Jew (1940) as a perfect example of Jewish degeneracy, using it to characterize all of the Jewish people and to justify its "criminal intents". Ultimately, we will never truly know whether

M is pro- or anti-Nazi. One thing is certain, though: Lang despised the society in which he lived (Ebert's parallel with

Cabaret - 1972 - in his review is beautifully illustrative).

|

| "What a pretty ball you have there!" |

The movie cast seems like a cross between the

Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and

Freaks (1932). In the first shot of the city, we are presented with a prostitute looking for clients, while all of its subsequent shots depict a grim and depressing Berlin, always at night. In interior takes, Lang makes sure we see the worst in every environment, reason why he makes closeups of greasy sausages, half-smoked cigars, burgling tools and stolen goods (there is a particular scene depicting a man hiding in the ladies' toilet to avoid the police which has no purpose other than to disgust the viewer). The population is described as apathetic and uncaring, as in

Se7en (1995), and, in their thirst for justice, is depicted as possessing a herd mentality. When policemen and criminals are seen scheming under a cloud of cigar smoke, each group in their own headquarter, the parallels between both meetings (as highlighted beautifully by

Paul Falkenberg's editing) induces the viewer to see both groups as equal, even though their motivations are paradoxically different - the former to protect society, and the latter to assail it.

Something that strikes me as astounding is that, overshadowed by Lang's brilliant directing and script, as well as by Lorre's heartfelt acting, editor

Paul Falkenberg is not given enough credit. Among several of his skillful scene transitions, the already mentioned parallel he accentuates between the assembly of the policemen and that of the criminals is a perfect example of masterfully used cross-cutting. Moreover,

M has, as far as I know, one of the earliest uses of subjective camera, in part the work of cinematographer

Fritz Arno Wagner, a very prominent figure in the German expressionist movement who collaborated with most of the great directors of the Weimar era. In the scene in which an old man, erroneously accused of being the killer, is confronted by his accuser, the old man, shot from a top-down perspective, seems exceedingly frail in comparison to his assailer, whose intimidating character is highlighted by being filmed from a bottom-up point of view. This contrast is made all the more pronounced by the way the whole take was assembled by Falkenberg, to the point that, when we finally see both men framed together, we are appalled to see that the difference in height existing between them is not nearly as big as we had anticipated.

|

| Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), the killer |

No character is more strongly associated with

M than

Peter Lorre's Hans Beckert. We first see him, or rather, his shadow, right at the beginning of the movie, while he is hunting for his 9th victim. We do not see his face right away; rather, Lang waits until we are fully aware of the ramifications of the murderer's acts to finally reveal his face to the audience. While a graphologist, after analyzing the killer's letters, can be heard stating that Beckert's psychopathy is intrinsically linked to many forms of

acting, we are finally shown the killer looking at himself in the mirror. My reasoning was then that, being Beckert a psychopath and thus not being able to feel empathy, he was practicing in front of the mirror how to

act as if he were smiling, giving up during the act as if realizing how pointless it all was. Ebert, on the other hand, interpreted this scene as the murderer trying to see in himself the monster everybody says he is, which is also a thought-provoking perspective. Not by coincidence, I have been reading a

book by S. Thomas about Peter Lorre in which she makes an extremely compelling point about that very scene: by the way the camera is positioned, we can clearly see the image of Beckert's face being distorted in the mirror while his actual face, given the angle it is being filmed, barely changes expression at all. This, according to her, is a way of conveying the internal transformation the murderer is subject to, appearing outwardly "normal" while, internally, turning into a monstrous character whenever his murderous desires are aroused. Cinematographer

Fritz Arno Wagner does indeed use reflections in several portions of the movie to express Beckert's inner emotions...

|

| The murderer is captured at last |

Like many talkies of its vintage (with

Dracula - 1931 - being arguably the most well known example), there is no soundtrack in

M, which Lang uses to his advantage:

by deliberately diminishing the variety of sounds we are made to hear, changing repeatedly from a world full of diegetic sounds to a complete silent one, he manages to make key scenes of the movie even more unnerving. Moreover, with this artifice, Lang also compels the viewer to associate Beckert's whistling, the only melody heard throughout the movie, with his compulsion to kill, making us dread whenever we hear it. Actually, since we almost never

see the killer whistling, were this not a talkie, the plot would become much more unintelligible, reason why, IMHO, in order to stress the importance of sound in

M, it is the blind beggar, who sees the world mainly through sounds, the one who first identifies the killer.

On top of it all, Lang and von Harbou still manage to cram some dark humor into their script. Besides an unexpected joke about a colorblind witness, I really liked Lohmann's mock interrogation of Franz (

Friedrich Gnaß), accusing him of accessory to the murder of one of the watchmen of the building he and his fellow criminals had broken into in order to look for Berckert, cutting from Franz's nervous smirk to a shot of the jolly "deceased" having a meal at home (kudos again to editor

Paul Falkenberg).

As Ebert adroitly put it in his review, "the film doesn't ask for sympathy for the killer Franz Becker, but it asks for understanding". Out of all the material I've ever read about M, I have never encountered a more pertinent way of describing it. Well done, sir. Well done.

Only a poet could put in words Peter Lorre's eloquence in his final monologue:

Comments

Post a Comment