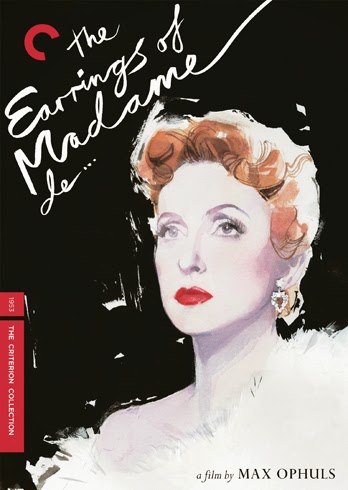

The Earrings of Madame de... (1953)

If someone asked me what was, in my opinion, one of the most damaging things to have ever happened to the movie industry, I would have replied, with no margin for doubt, the creation of the Hays Code in the US, in 1930, which laid out rules to which movies had to abide in order to be deemed "acceptable". In any other point in history, this code would have been quickly dismissed as the Puritan daydream it was; right after the Great Depression, however, movie executives were much more inclined to accept it, fearing boycotts to all "unacceptable" movies organized by e.g. the National Legion of Decency. As a result, during the 30 years that followed, movies in the US were required to uphold the sanctity of marriage, the rightness of the law and the sanctity of religion, aiming thus at "rebuilding human beings exhausted with the realities of life". There was no crime without punishment, nor a good deed without reward, and anything that could be construed as sexual was banned, aspiring hence to present the "correct standards of life" to the general public, even if that meant to completely disfigure the source material (like poor Betty Boop, or the ending of The Bad Seed - 1956). Luckily, far away from the self-righteous haven the US had become during the enforcing of Hays Code, filmmakers kept on questioning society instead of flattering it, dealing with controversial themes such as premarital sex - with Ingmar Bergman's It Rains on Our Love (1946) -, sacrilege - as in Roberto Rossellini's L'Amore (1948) - and the hypocrisy behind the so-called good moral values in society - similarly to Max Ophüls' La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1952) and The Earrings of Madame de...

The film begins with Comtesse Louise de... (Danielle Darrieux) browsing through her belongings. She is in great debt due to her extravagant lifestyle and, not wanting her husband, Général André de... (Charles Boyer), to know about it, settles on selling a pair of earrings for which she never cared much anyway, presented to her by André on the day of their marriage. In order to fool her husband, she pretends to have lost them at the Opera, unknowingly burdening the manager of the Opera house, who sees himself forced to post an article in the newspaper regarding a theft at the venue. The jeweler who bought the earrings, Monsieur Rémy (Jean Debucourt), afraid of the possible repercussions, sells the jewelry back to André, who, on his turn, gifts them to his mistress, on her way to Constantinople. In the meantime, Louise goes on with her frivolous lifestyle of gala balls, parties and younger lovers she likes to keep around to pamper her, until Baron Fabrizio Donati (Vittorio De Sica) makes her realize how meaningless her life had been, by making her fall in love with him. To symbolize their love, the Baron gives Louise a pair of earrings he had bought at a pawn shop in Constantinople - the same ones she had once sold to Mr. Rémy! André promptly recognizes the earrings as the one he had given to his mistress, hence being able to unmask Baron Donati (whom he knows had come from Constantinople) as Louise's lover. The Général then forces Louise to return him the earrings, and orders her and the Baron not to see each other again, to which the Baron, fearing for his own reputation, consents. Louise, still madly in love with the Baron, goes into a deep depression, selling nearly all her jewels in order to be able to buy her earrings back. Felling betrayed by Louise's love for the Baron, André challenges him to a duel, to which Louise, despite her feeble state, rushes to keep from happening. She is however too late; a single shot is heard: Louise falls unconscious by a tree, and her maid runs for help, screaming, "Help! Help! She's dying!".

|

| Louise de ... (Danielle Darrieux) and her husband André de... (Charles Boyer) going to sleep |

Louise is first presented to us as a futile woman with several lovers she meets with whenever her husband is away on maneuvers. André is fully aware of it, and he himself has mistresses. Extramarital relationships were commonplace at the time, provided they were within the limits of discretion (thus not hurting the dignity of their partners), and as long as they didn't fall in love with their paramours. In other words, Louise is not allowed to love Baron Donati, and the Baron, on his turn, is not permitted love her: Louise has to love, and Donati has to love -- making of "love" essentially an intransitive verb. Alas, Louise is not able to observe those rules and, terrified by this feeling she had never felt before, she tries to escape by travelling to the countryside, which only makes her long more and more for the Baron, whom she used to see regularly at balls. By allowing herself to be enthralled by the Baron, Louise hurts André's pride, and by refusing to play her role in society after her affair has ended, she wounds his dignity. This compels André to confront the Baron about the affair, after which Baron Donati, whose love, contrary to Louise's, is bound to intransitivity, promptly dismisses her. This does not shaken Louise's unconditional love for him, nonetheless, forcing André to challenge Donati for a duel so as to cleanse his honor, as dictated by the social decorum at the time.

The reason for the ellipsis in Mme. Louise de ...'s name is, IMHO, a twofold. First, it creates the illusion, so dear to 19th-century novelists, that their characters are based on real people. Second, the "filler" for that ellipsis is her husband's surname, with "de" loosely meaning "of" or "belonging to"; since Louise's heart has never "belonged" to André, the omission of his surname in hers further stresses the farcical nature of their marriage, as well as the fact that her earrings, when gifted by André, had nothing but commercial value to her. When the same earrings are given to her by Baron Donati, though, they acquire a deeply sentimental value, and this action becomes a turnpoint in the movie, whose atmosphere had been very cheerful up to that point. To emphasize this change of tone, Ophüls provides us, in the second half of the movie, plenty of counterparts to scenes in its first half. For example, when Louise first goes to the church and prays for her earrings to be bought by Mr. Rémy, she does so in a very perfunctory way, whereas at the end of the movie, praying for Donati to survive the duel, she is the polar opposite of her previous self, as illustrated by her framing with Sainte Geneviève, the patron saint of those afflicted by a catastrophe. Furthermore, by being, at first, a terribly vain woman, she makes sure to be dressed very elegantly and to keep a proper posture, fit to a woman of her quality, while talking to Mr. Rémy. Afterwards, frantic to reclaim her earrings, now a token of lost love, she no longer cares about her vanity, being willing to sell everything she own to be able to buy them back. Moreover, there is always a laugh whenever Mr. Rémy returns to André to sell him back the earrings... except after those earrings have become a reminder of the deep love his wife feels for the Baron, when there are no more grins to be had.

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Again back to the theme of scene parallels, Danielle

Darrieux is commendable in her portray of Louise's

character arc. Notice her facial expressions and overall posture at the beginning (on the left) and at the end of the film (on the right). | |||||

With The Earrings of Madame de... being a study on the frivolousness of a marriage without love, it is only natural for Baron Donati to (intentionally) be the blandest of the three main characters. He is struck by Louise upon seeing her for the first time, but that infatuation is promptly set aside when his honor as a gentleman is challenged by the Général. Louise and André, on the other hand, are both much more well developed (again, as expected), with Charles Boyer's character arc being more introspective than Danielle Darrieux's. Take for instance Louise's fainting spells, an expected trait of any respectable 19th century woman: when she is, as usual, dissimulating a spell to get her way, notice, in the still above, how she struggles to remain attractive to Mr. Rémy, with her perfect posture and archetypal "fainting face". Now, compare it to the still on the right, when she really faints, worried sick about the Baron she had just seen fall from his horse: observe her arched back and her sagging neck, not at all glamorous. That real fainting spell lasts for more than the stipulated three minutes, which "is what befits a woman of good breeding" according to André. Despite feeling something is out of place, it is not until he sees Louise wearing her "lost" earrings, however, that André is able to grasp the situation and, for the first time, he feels threatened. Louise may have had lovers, as he certainly has had, but she belongs to him, her heart included. Her unconditional love for the Baron is, therefore, an affront to his honor, which he intends to wipe out with the Baron's blood and, in the process, cure Louise of her "illness". The fact that Louise (apparently) dies as a result is a display of Ophüls' poetic justice.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

| Scene parallels are once more used to contrast the loving way Général André treats his mistress (on the left) and his cold, mechanical attitude toward his wife, Louise (on the right) | |

Général André is not an evil man; he is merely a product of his time. He is friendly toward Louise and gives her money for clothes and jewelry, but spends his days in the army and his nights in gala balls or with his friends at the gentlemen's club. He says to himself that he loves her, and maybe he did once, but now André and Louise are strangers living together under the same roof. Once again Ophüls makes use of scene parallels to contrast André's attitude toward his mistress and his wife: whereas he acts very lovingly in the presence of the former, his attitude toward the latter is mechanical and cold, feeling almost like a chore. While there is permanent eye and body contact between him and his mistress, he and his wife barely exchange glances throughout the entire scene, culminating in a heartbreaking shot in which André cannot make himself kiss Louise good-bye.

That is not to say the movie is not without its flaws. For instance, since the focus of the film is Louise's evolution as a human being, I can understand that not too much time was spent in her courting by the Baron, summarized instead in several (exquisitely edited) takes of them dancing. What I find it hard to believe, however, is the fact that the Baron bought such madly expensive earrings on a whim, with the sole purpose of offering them to any woman he might come to love in the future! Remember that, in order to purchase those earrings back, Louise, a rich woman, had to sell all her jewels and furs... Is the Baron really that wealthy? Other than that, the "the offended party fires first" rule in the duel pretty much turns it into an execution, entirely removing the suspense and anticipation of its outcome, making the ending of the movie much less ambiguous than I expected.

| Liked | Didn't like |

|---|---|

| The cheeky ways with which the script deals with Louise's never revealing her full name are quite enjoyable | Would the Baron really buy jewelry that expensive on a whim? |

| Every frame Charles Boyer shares with Danielle Darrieux | I wonder where the rules for the duel between the Baron and the Général came from... |

One of the most beautiful shots in the movie:

Great Movie review by Roger Ebert here.

If you liked this movie, then maybe try watching Ophüls' La Ronde (1950).

Comments

Post a Comment