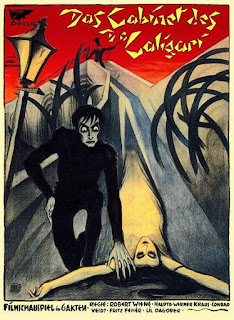

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

The history of the Weimar Republic is as short as it is fascinating. Established in 1918-19 by reformist civilian politicians who aimed at introducing modern democracy to a Germany used to nothing but the authoritarian Hohenzollern monarchy, its formative years were far from the democratic-republicanist utopia its creators had aspired. With its economy crippled by the maintenance of the blockades imposed during World War I, famine was generalized; the humiliating terms of the Treaty of Versailles infuriated right-wing extremists, who brewed hate and antisemitism; political instability caused by power struggles among several party coalitions made it nearly impossible to run the young republic efficiently; lastly, the German people, once suppressed by absolute state power, commanded to follow and obey, felt severely at a loss about their newly given rights, retreating instead into themselves, yearning for a strong leader to show them the way. In this atmosphere of uncertainty and pessimism, an art form that emphasized one’s inner feelings over replicating the real world, Expressionism, was brought back to the limelight. Originated in Germany in 1905 from the optimism of young artists who antagonized the material restraints of their contemporary bourgeois society, post-WWI Expressionism on the other hand focused on the social and political issues of the common man traumatized by the war and embittered by its aftermath. This is why, even though artists in both periods shared the desire to move beyond the limitations of objective subject matter, seeking rather to reveal inner, spiritual and emotional foundations of human existence, the latter generation dealt mainly with the themes of madness, tyranny, crime, social decay and the destructive power of money. Although its impact in Weimar theater, dance, architecture and painting could be broadly felt, it was on film that Expressionism would reach mass appeal, with a 71-minutes, low-budget movie becoming so influential that it alone helped break the ban on German films across the globe, unofficially instated after the war. That movie was Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Most of the movie is told in flashback, as Francis (Friedrich Feher) narrates to an unspecified man the terrible things he and his fiancée, Jane (Lil Dagover), had experienced not so long ago in their city of Holstenwall. We are then transported into his story, being introduced to his friend Alan (Hans Heinrich von Twardowski) as they decide to go to the annual carnival that had just come to town. That year, a sinister-looking man called Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss) had also come with the troupe, exhibiting his somnambulist, Cesare (Conrad Veidt), who, he says, can predict the future. Intrigued by the premise, Allan decides to take part in the act, jokingly asking how long he had yet to live, being told by the somnambulist he would be dead by dawn. In the following morning, as predicted, Allan is found dead. Upon receiving the news of his friend's demise, Francis promptly suspects Cesare, bringing Jane's father, Dr. Olsen (Rudolf Lettinger), to examine him at Caligari's hut, but their search is to no avail, as they are mislead into thinking the killer had just been captured by the police. The following night, a menacing Cesare is depicted slithering along the walls of the city, on his way to Jane's house. He barges in through her bedroom window with the intent of killing her, but, lovestruck by her beauty, kidnaps her instead. Awoken by the commotion, the townspeople chase the sleepwalker as he flees though the rooftops with Jane on his arms, but, with his lethargic body not being able to bare her weight any longer, he dies of exhaustion. When confronted about the incident by the police, Caligari manages to escape, seeking refuge in a nearby insane asylum. He is closely followed by Francis, who, upon further investigation, learns that the doctor is actually that asylum's director, and that, obsessed with somnambulism and an 18th century mystic named Caligari, had decided to adopt that name and use Cesare, his patient, as a pawn to commit a series of murders. He then brings the police to the asylum, taking Cesare's body along with them. The doctor, upon seeing his slave dead, is overtaken by madness, thus becoming a patient in his own sanatorium. We finally come back to the present, discovering, to our surprise, that Francis is in fact a patient in that mental institution, which is run by the doctor he claims to be Caligari. In his delusion, he attacks the doctor on sight, accusing him of being the murder in his fantasy. The doctor then, finally understanding the cause of Francis's breakdown, announces he can finally cure him.

After having (finally!) been able to get my hands on Kino's wonderful 4K restoration of Robert Wiene's masterpiece, I felt compelled to rewrite the (rather shallow) overview of the film I wrote a couple of years ago, such was the impact of seeing the work of production designers Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig in all its glory. In being Expressionist artists, they approached Wiene early in the production about building the movie sets Expressionistically, to which the director promptly agreed, believing such art style to be perfectly suited for evoking the foreboding mood he desired. Producer Erich Pommer, too, was supportive of such artistic direction, as he believed art assured export, and export meant salvation, as an impoverished UFA could by no means compete directly with movies from other countries. On top of that, he knew that, by having all shadows painted on the abstractly designed sets, he could greatly save on production costs, since electricity in post-war Germany was rationed and quite expensive. As a result of their work, through Expressionism, the characters of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari seem to inhabit a twisted, menacing world, in which assassins and madmen may lurk at every corner, and authority figures literally look down upon the common people. Such environment is, interestingly, contrasted sharply to Jane's home, the set in the movie in which Expressionism is used with the most restraint. Rather, that set is furnished with familiar objects whose natural symmetry is respected, feeling because of that strangely comforting and familiar when contrasted to the askewness and hostility of the outside world. Instead of either yellow (day) or blue (night) tinting, depictions of her house are veiled by a soft pink tone, further contributing to the ethereal look of that particular interior (perhaps thus mirroring the collective retreat into a shell allegedly experienced by the German people during those troubled times?). Its production designers also pioneered on film the use of chiaroscuro lighting for depicting stark contrasts between light and shadow, a technique that some decades late would greatly influence the aesthetics of film noir.

No discussion on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari would be complete without mentioning Siegfried Kracauer's highly influential book From Caligari to Hitler. Published in 1947, it was the main responsible for maintaining interest in Weimar cinema at a time when its film history could not be studied in any detail. In a lengthy chapter about the movie, Kracauer talks at length about the original intent of story and how it was butchered by Wiene, basing his thesis on direct testimony by one of its two screenwriters, Hans Janowitz. Kracauer starts by reporting on how, after having served the war effort, both writers had become convicted pacifists, animated by hatred of an authority which had sent millions of men to death. As a result, they produced a script that, originally, exposed the madness inherent in that authority, embodied in Caligari, that did nothing but exploit the common man, in the form of Cesare. He then laments that Wiene felt forced to answer to mass desires by softening its revolutionary tone, bookending it with a frame that, he states, imbued it with a meaning opposite to the one its authors had intended: Wiene's version, rather, glorified authority and ironically convicted its antagonist of madness -- a conclusion to which the authors vehemently opposed, as remarked by Janowitz. In this way, by reducing Wiene's contribution to the movie to nothing but a frame which dishonored its original intent, Kracauer's book greatly damaged its director's reputation, to the point where his authorship of the movie has often been challenged since then. Thankfully, in recent years several film scholars have come to Wienes's defense, most recently Uli Jung and Walter Schatzberg with their book Beyond Caligari: The Films of Robert Wiene (1999), in which they state that Kracauer's greatest mistake was to uncritically accept Janowitz's account, bound to be biased toward him and his fellow scriptwriter. They support this claim with solid evidence instead of just testimony, most notably the original draft of the script, which was released as a book only in 1995. In it, it can be seen that the final draft of the script, the one sold to the producers, has also been bookended - something Janowitz seems to have failed to tell Kracauer -, albeit differently. According to Jung and Schatzberg,

"In the original frame story, twenty year after the events, Francis and Jane live as a married couple in comfortable circumstances, with Francis then telling the story to their guests. Here, no revolutionary intent is possible, nor there is any social criticism involved: the social standing of the narrator, the acceptance of bourgeois conventions, the twenty-year detachment from the events, and the accidental occasion for their recollections can hardly serve as an effective frame for a tale with revolutionary force."

One thing that both the original and the final script had in common was their emphasis on Dr. Caligari's character, developing it more than any other and, in this way, giving ample room for Werner Krauss to dazzle us with his beautifully expressive pantomime. His physicalization of Caligari is at his best whenever he appears alongside Conrad Veidt's (purposely) cold and distant Cesare, as the latter's lethargy seems to highlight the former's delightful overacting. Both actors would share the screen again in Henrik Galeen's haunting The Student of Prague (1926), before being forever separated by their political ideologies, as Krauss became an avid member of the Nazi party, while Veidt fled to England once the Nazis took over Germany. Coincidentally, they both appeared in film adaptations of the 1925 novel Jud Süß by Lion Feuchtwanger, about a Jewish merchant who becomes the advisor of the Duke of Württemberg, with Krauss's 1940 version demonizing the Jewish people whereas Veidt's 1934 adaptation, closer to the original novel, had no such subtext. Once the Second Wold War ended and the Nazi regime fell, Krauss was ostracized by the intentional community (and, contrary to Leni Riefenstahl, rightfully so), never being able to act again.

Robert Wiene returned to Expressionism with his under-appreciated Raskolnikow (1923), but, by then, Expressionism in movies had all but faded, giving room to camera tricks, special effects and more advanced lighting techniques. As for the Weimar dream, it was given a glimmer of hope thanks to Gustav Stresemann from 1924 to 1929, when the Great Depression brought it to a crashing halt -- and we all know what came from that...

Great Movie review by Roger Ebert here.

If you liked this movie, then do watch Victor Sjöström's The Phantom Carriage (1921), as well as F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (1926).

Most of the movie is told in flashback, as Francis (Friedrich Feher) narrates to an unspecified man the terrible things he and his fiancée, Jane (Lil Dagover), had experienced not so long ago in their city of Holstenwall. We are then transported into his story, being introduced to his friend Alan (Hans Heinrich von Twardowski) as they decide to go to the annual carnival that had just come to town. That year, a sinister-looking man called Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss) had also come with the troupe, exhibiting his somnambulist, Cesare (Conrad Veidt), who, he says, can predict the future. Intrigued by the premise, Allan decides to take part in the act, jokingly asking how long he had yet to live, being told by the somnambulist he would be dead by dawn. In the following morning, as predicted, Allan is found dead. Upon receiving the news of his friend's demise, Francis promptly suspects Cesare, bringing Jane's father, Dr. Olsen (Rudolf Lettinger), to examine him at Caligari's hut, but their search is to no avail, as they are mislead into thinking the killer had just been captured by the police. The following night, a menacing Cesare is depicted slithering along the walls of the city, on his way to Jane's house. He barges in through her bedroom window with the intent of killing her, but, lovestruck by her beauty, kidnaps her instead. Awoken by the commotion, the townspeople chase the sleepwalker as he flees though the rooftops with Jane on his arms, but, with his lethargic body not being able to bare her weight any longer, he dies of exhaustion. When confronted about the incident by the police, Caligari manages to escape, seeking refuge in a nearby insane asylum. He is closely followed by Francis, who, upon further investigation, learns that the doctor is actually that asylum's director, and that, obsessed with somnambulism and an 18th century mystic named Caligari, had decided to adopt that name and use Cesare, his patient, as a pawn to commit a series of murders. He then brings the police to the asylum, taking Cesare's body along with them. The doctor, upon seeing his slave dead, is overtaken by madness, thus becoming a patient in his own sanatorium. We finally come back to the present, discovering, to our surprise, that Francis is in fact a patient in that mental institution, which is run by the doctor he claims to be Caligari. In his delusion, he attacks the doctor on sight, accusing him of being the murder in his fantasy. The doctor then, finally understanding the cause of Francis's breakdown, announces he can finally cure him.

|

| Caligari (Werner Krauss) being shun away by the town clerk |

No discussion on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari would be complete without mentioning Siegfried Kracauer's highly influential book From Caligari to Hitler. Published in 1947, it was the main responsible for maintaining interest in Weimar cinema at a time when its film history could not be studied in any detail. In a lengthy chapter about the movie, Kracauer talks at length about the original intent of story and how it was butchered by Wiene, basing his thesis on direct testimony by one of its two screenwriters, Hans Janowitz. Kracauer starts by reporting on how, after having served the war effort, both writers had become convicted pacifists, animated by hatred of an authority which had sent millions of men to death. As a result, they produced a script that, originally, exposed the madness inherent in that authority, embodied in Caligari, that did nothing but exploit the common man, in the form of Cesare. He then laments that Wiene felt forced to answer to mass desires by softening its revolutionary tone, bookending it with a frame that, he states, imbued it with a meaning opposite to the one its authors had intended: Wiene's version, rather, glorified authority and ironically convicted its antagonist of madness -- a conclusion to which the authors vehemently opposed, as remarked by Janowitz. In this way, by reducing Wiene's contribution to the movie to nothing but a frame which dishonored its original intent, Kracauer's book greatly damaged its director's reputation, to the point where his authorship of the movie has often been challenged since then. Thankfully, in recent years several film scholars have come to Wienes's defense, most recently Uli Jung and Walter Schatzberg with their book Beyond Caligari: The Films of Robert Wiene (1999), in which they state that Kracauer's greatest mistake was to uncritically accept Janowitz's account, bound to be biased toward him and his fellow scriptwriter. They support this claim with solid evidence instead of just testimony, most notably the original draft of the script, which was released as a book only in 1995. In it, it can be seen that the final draft of the script, the one sold to the producers, has also been bookended - something Janowitz seems to have failed to tell Kracauer -, albeit differently. According to Jung and Schatzberg,

|

| Wiene's depiction of Allan's murder |

Thus, Kracauer and Janowitz's claim that, without a frame, the film would have been "more powerful, more honest, more revealing" clearly does not hold. Furthermore, Jung and Schatzberg also refer to a contract signed by both scriptwriters in which not only they agreed to the changes in the manuscript prior to the film's production, but also sold the rights to a novelization of the finished film, leaving no room for their ideological opposition to the revisions deemed necessary by UFA, as denounced by Janowitz. Since no trace of revolutionary attitudes can be seen in the original draft of the scrip, yet they are interpreted to be present in the finished film, it is thus clearly thanks to its director's handling of the production, Jung and Schatzberg advocate. They support Wiene's authorship of the movie by listing several instances in which the better judgement of the director helped improve on the writer's storytelling. For instance, Wiene completely changed the dynamic of the love triangle between the main characters, which led to the suppression of a vision of Allan's ghost shared by Francis and Jane. He considered such apparitions more appropriate to a neoromantic atmosphere, and thus in opposition to the realistic-yet-unsettling, mood he and the art directors were trying to achieve. Wiene was also able to eliminate several lengthy title cards contained in the script, the authors state, via either cross-cutting (as in when Francis is keeping watch on Caligari and what it resembles a sleeping Cesare, while the real Cesare goes after Jane) and his handling of the actors (remark the beauty of the scene in which Francis tells Jane about Allan's murder, in which no intertitles are needed). About the controversial framing of the story, Jung and Schatzberg state that replacing the happy ending intended by the screenwriters in favor of a bleak resolution was indeed part of Wiene's narrative strategy, so that the traumatic events we tough had been resolved have us in their grip once more, arguing that it improves on the lingering impact of the film. Having not yet read the original script, I am unfortunately unable to opine...

|

| Caligari upon first meeting the somnambulist Cesare, after having obsessed over that illness for so long |

Robert Wiene returned to Expressionism with his under-appreciated Raskolnikow (1923), but, by then, Expressionism in movies had all but faded, giving room to camera tricks, special effects and more advanced lighting techniques. As for the Weimar dream, it was given a glimmer of hope thanks to Gustav Stresemann from 1924 to 1929, when the Great Depression brought it to a crashing halt -- and we all know what came from that...

Summarizing it:

Liked

|

Didn't like

|

|---|---|

| Aesthetically unforgettable | Rather short |

| Werner Krauss's Caligari | |

Thanks to Kino Lorber's fantastic restoration work, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari has never looked so stunning:

Great Movie review by Roger Ebert here.

If you liked this movie, then do watch Victor Sjöström's The Phantom Carriage (1921), as well as F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (1926).

Comments

Post a Comment